Reverse engineering a car head unit faceplate

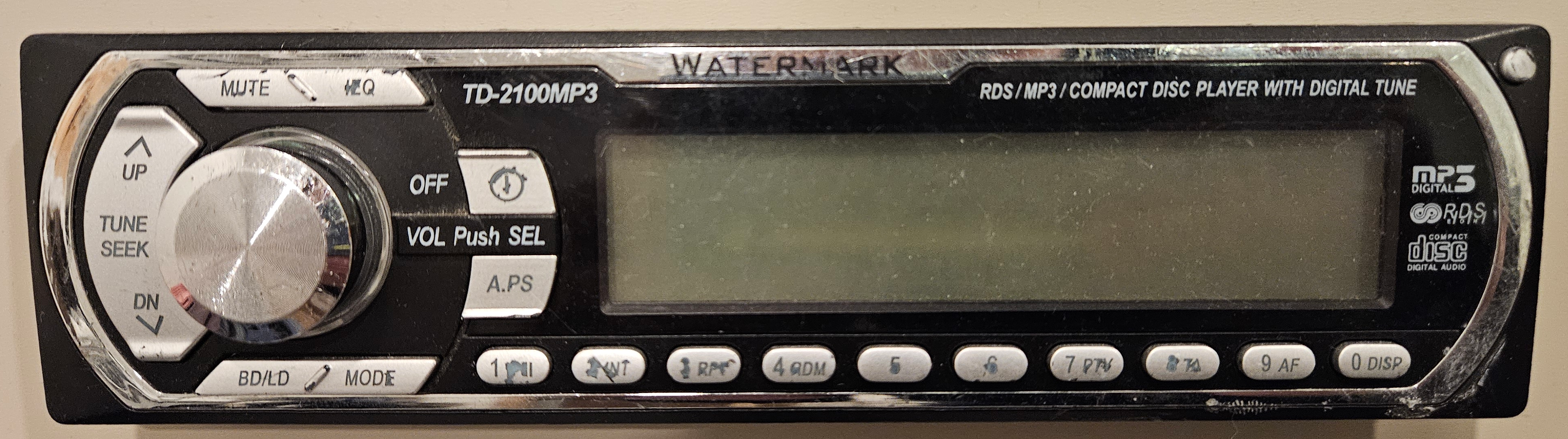

Sometimes, a thing appears in your junk box out of nowhere. It’s utterly pointless, but you can’t bring yourself to throw it away (to the recycling center, of course!) because a though resides in your head - “Hey, I might need that some day for a project”. This is a story of such item. Around a decade ago, a faceplate for a Watermark TD-2100MP3 car head unit appeared in my junk box (pictured below). I can’t remember where I got it from, but I always thought it would be fun to figure out how one works and turn it into a nifty user interface for some project. As any good engineer, for every thousand projects I start, around 0.24 make it till completion. And I usually do user interfaces last, so you can see why it sat there for so long.

But before going into the technical bits, here’s some history.

For the youngsters - Why did car radios have a face plates?

In the 90’s, a time when the Internet was very young, West Coast beefed with East Coast and a certain wall in Europe fell, cars used to come with radios that were … shit, to put it bluntly. And by shit, I mean lacking in features, having poor audio quality, not blasting enough bass to shatter windows of the entire street and things of that nature. But here’s the thing, as of mid 80’s, all car head units (even to this day) use standard form factors, outlined by the ISO 7736 standard. This is great for the end user, because where OEM manufacturers fail, folks like Sony, Pioneer, Kenwood, Alpine and many others come in, offering upgrades, such as CDs in the era of casettes (and then later MP3 CDs), USB support (from mid 2000’s-ish), external amplifiers and enough blue LEDs to blind everybody in a kilometer radius.

And where I come from, back in the day, having a Kenwood or an Alpine was a status symbol. That made them a prime target for thieves. The thing is - stealing a radio ain’t that hard. Smash a window , open the door, yank the damn thing out (since nobody bothered to actually screw the radios in properly), then briskly walk away whistling a tune, since nobody cares about blaring car alarms or shatter sounds anyway.

To combat this, manufacturers came up with an “ingenious” solution - make the front of the radio (the bit that has the screen and the buttons, hence a faceplate) removable, so you could take it with you when you leave the car. The theory being that it would make the radio worthless, since it would be missing a major component. I mean it was the 90’s, the design meetings probably involved ecstasy with Aphex Twin or The Chemical Brothers blaring in the background. In practice, people either didn’t remove them or just chucked them into the glove box as it was inconvenient to carry that bulky piece of plastic around. And that’s where thieves checked first. Even if people took the faceplates with them, they usually lacked any sort of pairing mechanism, meaning you could just acquire a faceplate (it wasn’t that hard) and use it with a radio of a matching type.

Needless to say, thats why these things died out. But it’s still a cool bit of electronics that’s worth exploring.

The Hardware

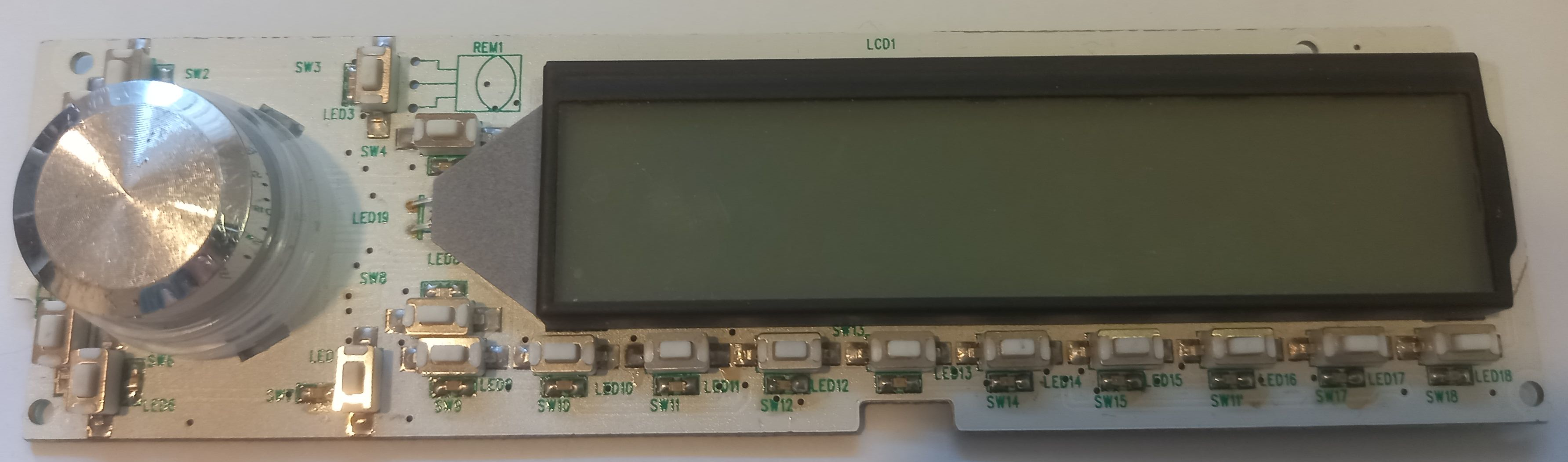

Let’s look at the unit that I have. First of all, taking the thing apart was far too easy, considering that its intention is to be a security device of sorts. I just undid a couple of Phillips screws on the back and it popped right open. The insides were unsurprising as well - a simple PCB, with a screen, rotary encoder, buttons and LEDs on one side:

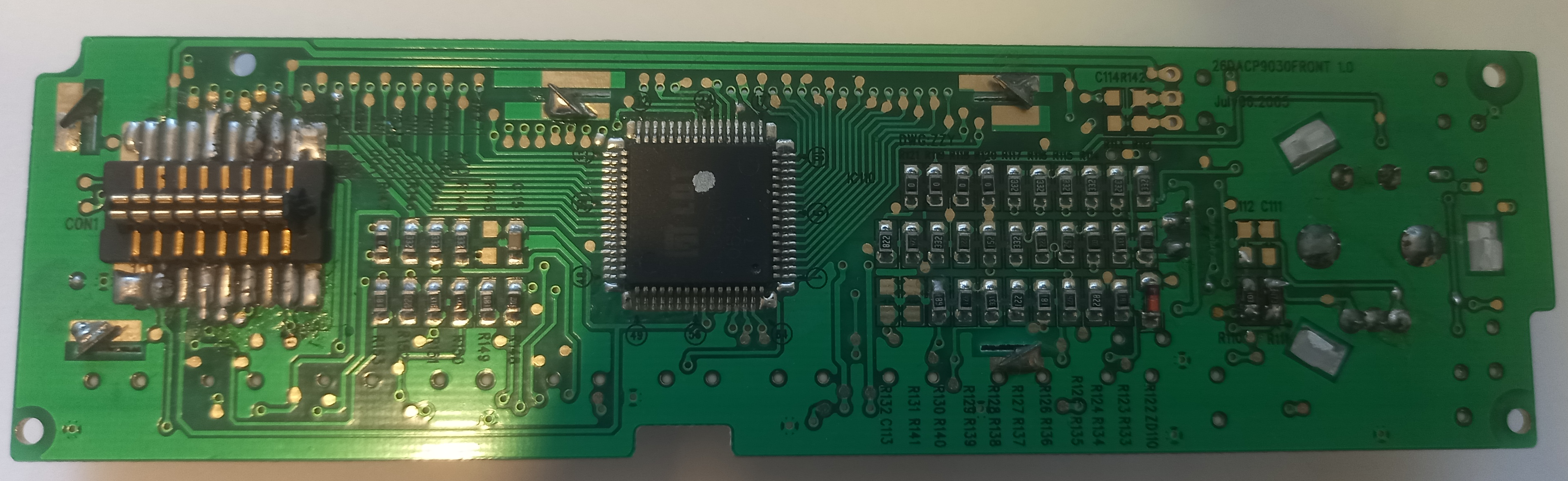

And a single IC, a single diode and a hand full of passives on the back:

If my camera weren’t so shit, you would also be able to see that there is a neat pin-out of the connector on the top left corner of the PCB (near the connector), which reads as follows:

| GND | GND |

| KY1 | REM |

| VDD | NC |

| VOLB | VOL |

| KY2 | NC |

| CE | INH |

| GND | DATA |

| CLK | LAMP |

Some of these pins on the connector are self explanatory, some are not. To get a full picture of the pinout and an idea of how to interface with this thing, I chose to reverse engineer each individual “subsystem” (if we can call it that).

The mystery IC

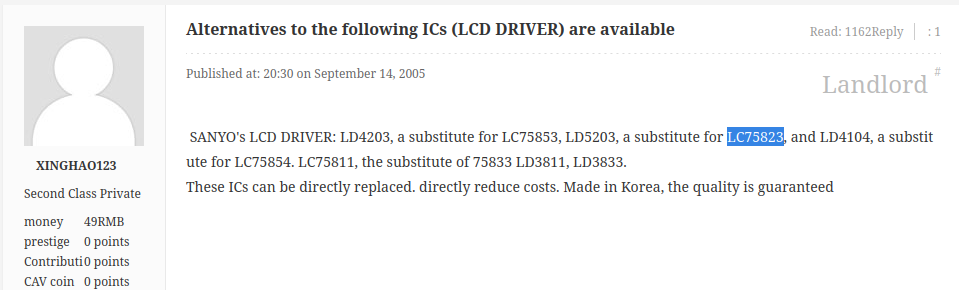

I tackled the IC first. My line of thinking was, that if it’s a microcontroller, it will probably be connected to everything and I will need to dump its firmware to get a clue of its inner workings. Looking closely, it bears a marking of LDT LD5203. Dropping that model number into a search engine yields nothing of value, except for some sketchy shops to buy the IC from. No datasheet, not even allusions to its purpose. So I had to get my hands dirty and search for variation of the IC name + some keyword. After a few grueling hours, I stumbled on to this in an obscure Chinese forum:

This was an important finding, revealing that the mystery LDT LD5203 is a clone of the Sanyo LC75823E LCD display driver, which is a pretty common chip and it’s datasheet is readily available. I was able to validate this claim pretty easily using the method described below. Thanks XINGHAO123!

Looking at the datasheet of the Sanyo IC, I found that communication to a microcontroller is done using something called CCB (computer control bus, invented by Sanyo of course). In practice it is nothing more than one-way SPI, where an address of a particular device on the bus is sent first and its chip select is inverted and toggled at different times.

The IC also has an INH pin, which turns the LCD display off, yet still allows receiving commands over CCB. It is routed to the INH pin on the connector. After confirming the wiring with a multimeter in continuity mode, I was able to figure out that INH, CE, DATA and CLK pins on the connector are used to drive this LCD controller IC.

Buttons

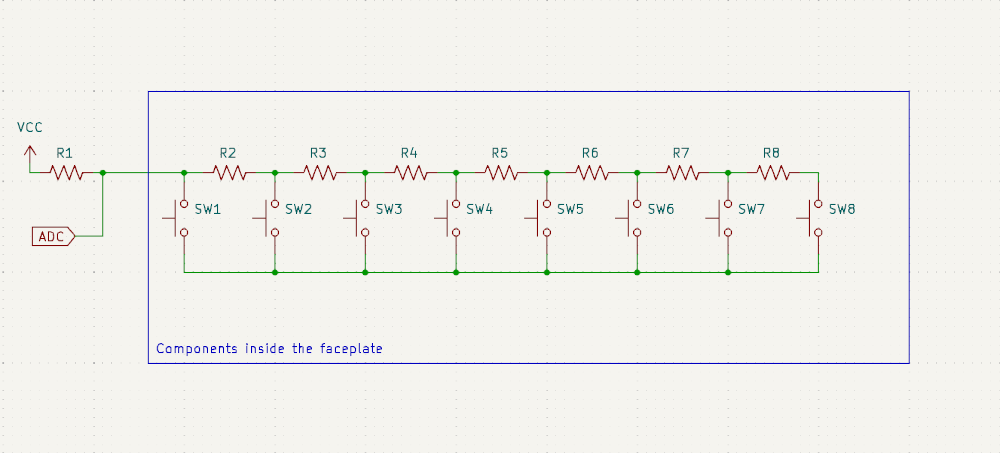

If you gaze your eyes to the first picture in this article, you can see that there are quite a few buttons on the faceplate. Yet, there aren’t enough pins for all of them. In fact, there are only two pins dedicated for buttons: KY1 and KY2. And to get data from them, a pretty neat trick is used - a resistor ladder with buttons. Let me explain the concept with a schematic:

First of all, this method requires an ADC (analog to digital converter) and a pull up resistor. Combined, the circuit forms a variable voltage divider of sorts. As you progress through the buttons, the amount of resistors connected between ground and pull up resistor changes. Sample the data at the outlined branch then use a pre-computed look up table (depends on the values of resistors) and you can determine which button was pressed pretty reliably.

The faceplate in question has two banks of buttons, hence KY1 and KY2. Since ADCs are of fixed resolution, there are limits to how much buttons you can connect in a single bank. Also, this method allows only one key press to be detected at a time. If you press multiple buttons, only the closest one to the pull up resistor will be detected, because that’s where the closest connection to ground is. This may also be a reason why buttons are split into two banks - to allow a combination of buttons to be pressed at the same time on different banks. Since I don’t have the radio itself, I can’t check if such combinations actually exist.

Side note: If you plan on using this technique in your own designs, be careful when using pull up resistors that are built into MCUs. Initially, this may sound like a good idea, but they can be pretty inaccurate and that messes up your look up table.

The rotary encoder

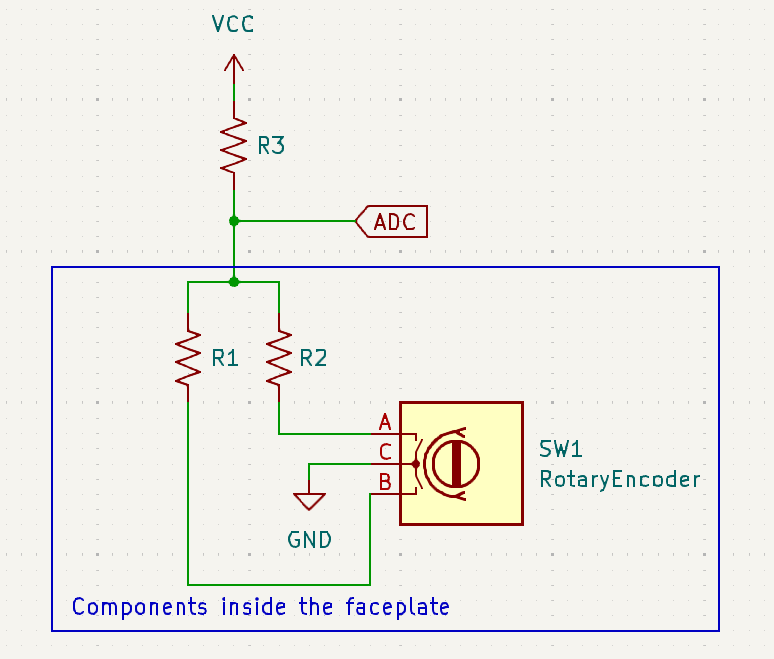

Rotary encoder was an interesting one. I quickly traced that it is wired through VOL and VOLB pins of the connector. But it didn’t make any sense, as they were both shorted. Even looking at the PCB, you can see that VOL and VOLB are connected (sadly, can not be seen in posted pictures). So, what gives? Well, a same trick is used as with buttons - a resistor-ladder like thing, whose schematic is shown below:

The way that a rotary encoder works is by generating two square-ish waves that have a 90 degree phase difference between them. Depending on which signal is leading, you can determine the rotation direction. Counting the number of edges reveals how many “clicks” of the encoder were made. Wikipedia has a really nice article on the inner workings of these things.

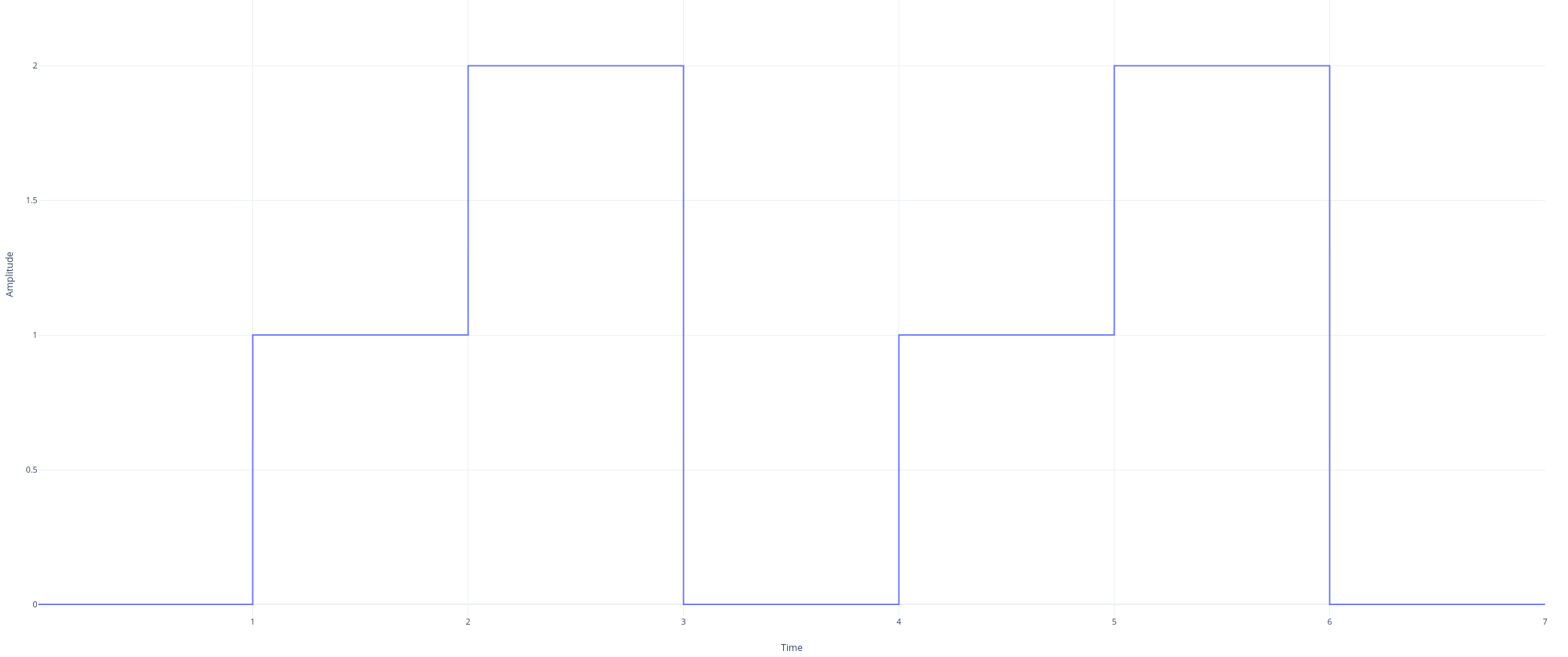

When resistors are connected as shown in the diagram, signal looks something like this (of course, it all depends on resistor values):

The way you determine direction and number of “clicks” is a bit more difficult than the typical way of handling rotary encoders. First of all, notice that there are three distinct voltage levels: low, mid and high. And turning clockwise (let’s say, this is all relative and depends on how the encoder is wired), the sequence is: low, mid, high, low, mid, high. This means, that if a transition from low to mid, from mid to high or from high to low happened, a “click” in a clockwise direction was made. Coincidentally, if a transition from low to high, high to mid or mid to low happened, a “click” in a counter-clockwise direction was made.

As with buttons, this requires constant sampling using an ADC and a look up table programmed as described in the paragraph above. That way, you can reliably determine the number of “clicks” and in which direction were made just by looking at what transitions happened.

Of course, debouncing was needed for buttons and the rotary encoder to get a quality signal. A different way of connecting things does not eliminate switch bouncing.

The remaining stuff

There are still a few unknown pins left on the connector. First, the self explanatory ones - VDD and GND. That’s voltage and ground. Referring to the datasheet of the LCD controller, I deduced that it works with 5 volts. NC is no connect and a lack of trace is quite clearly visible when looking closer at the PCB. LAMP is pretty obvious too - its for the LED backlight. I measured the current consumption @ 5V and it was below 10 mA. Meaning, it is pretty safe to drive directly from a microcontroller. The light output was sufficient too. By using a PWM enabled output, brightness control can be implemented trivially.

There is only one remaining - REM. If you take a look to the picture of the front of the PCB, there is an unpopulated component in the top left corner between SW3 and SW4 - an IR receiver. I suspect that a higher-end model of this head unit had a remote controller, but for this particular one - it is not fitted. A quick test with a multimeter on continuity revealed that one of the pins from the unpopulated component is wired to the REM pin. So for this particular face plate, REM is for all intents and purposes another no connect.

Figuring out display segments

Knowing how the display is driven is only a part of the equation. I still don’t know how the LCD itself is wired to the driver IC. This is important, as it dictates what data must be sent to the LCD driver in order to output useful information.

Turning the display at an odd angle and shining a light from a flashlight revealed to me that the display has:

- 8 13-segment displays (a variation of the 14-segment display with i and l segments merged into a single one)

- a single 7-segment display

- a handful of symbols

- a few collection of symbols intended for animations (i.e. a spinning CD and such)

My task is clear here - figure out how to turn on each segment individually. I opted to use an ancient Arduino Duemilanove for this task (because I needed a 5V compatible device). I connected DATA and CLK pins to SPI, CE to a regular GPIO pin and I tied INH low to always enable the screen. Power was also supplied via VDD and GND pins to the faceplate from the Arduino.

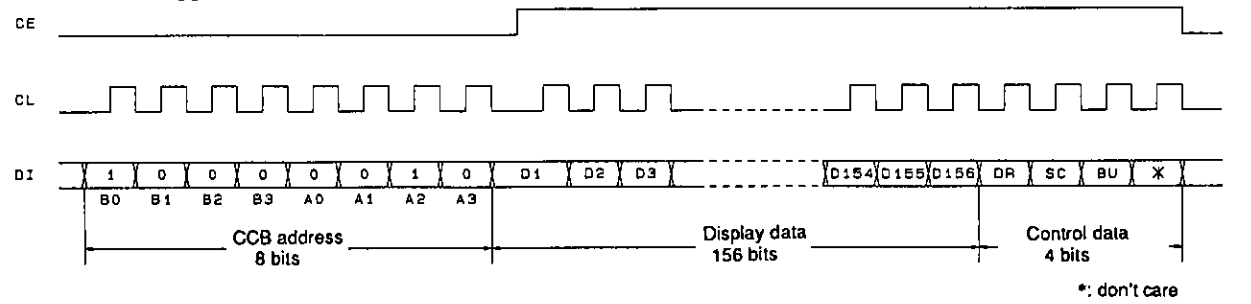

The first order of business is to implement the CCB protocol. The datasheet has this handy diagram:

According to this timing diagram, the microcontroller has to:

- Write the CCB address of the target IC (

0x41in this particular case) - Set CE pin to HIGH

- Write 156 bits of display data

- Write 4 bits of control data (technically, it’s three data bits and a single “don’t care” bit)

- Set CE pin to LOW

Each byte is clocked on the rising edge. The entire transaction is 21 bytes. Note, that the data is written with least significant bit first. This is important for stuff like the address (as 0x41 becomes 0x82) and control data. But for display data - less so, as you will see later.

Anyway, here’s the code to do a CCB transaction using the Arduino SPI library:

void write_segments(uint8_t address, uint8_t data[seg_count])

{

uint8_t data_cpy[seg_count];

memcpy(data_cpy, data, seg_count);

SPI.begin();

SPI.transfer(&address, sizeof(address));

digitalWrite(CE, 1);

SPI.transfer(data_cpy, seg_count);

digitalWrite(CE, 0);

SPI.end();

}

Now, to build the transaction. First of all, every single bit in control data can be set to 0. This disables power saving mode, enables the display and sets the correct bias drive.

As for display data, each bit represents a segment on the display. I initially memset’d all segment data to 1 and sent it to the controller - every single segment lit up on the display. This was a breakthrough as it not only confirmed that I had the correct datasheet (the forum post was correct!), but it also told me that I implemented the protocol correctly. Now comes the hard part - mapping each bit in the display data to a specific segment. To make working with the data easier, I developed an abstraction and its corresponding functions which allow me to map a single segment to a byte and bit offset which I named segment address:

struct seg_address

{

uint8_t byte : 5;

uint8_t bit : 3;

};

void clear_bit(seg_address addr, uint8_t data[seg_count])

{

data[addr.byte] &= ~(1 << addr.bit);

}

void set_bit(seg_address addr, uint8_t data[seg_count])

{

data[addr.byte] |= (1 << addr.bit);

}

This abstraction lets me ignore the fact that the data needs to be sent least significant bit first, as a particular segment just becomes a different byte and bit combination. This abstraction also has another advantage, which will be described below. Mapping each segment on the display was a laborious process. What I did was manually increment bit and byte components of segment address and noted which segments on the display lit up. At the end of this process, I knew how the segments of the LCD are mapped, but I still was not satisfied.

As mentioned before, there are various symbols on the display, which are trivial to control - they are either on or off. More complex are animation symbols and the 7-segment display, but they are manageable too as they are unique and can be controlled using a look up table. But a problem arises with 13-segment displays, as it requires storing some data to display digits and letters. There are 8 13-segment digits on the display and storing entire symbol table (all representable digits and letters) for each individual 13-segment display would be a waste of memory. I wanted to have just one symbol table and then apply it to each 13-segment digit based on its position. To accomplish this, I needed to figure out a pattern by which a segment address changes as you move down each individual 13-segment display. Initially, I noted down each coordinate of the center bar (combination of i and l segments) in the 13-digit display. The addresses are as follows:

| 13-segment display | Address (byte:bit) |

|---|---|

| 1 | 0:0 |

| 2 | 2:1 |

| 3 | 4:2 |

| 4 | 6:3 |

| 5 | 8:4 |

| 6 | 10:5 |

| 7 | 12:6 |

| 8 | 14:7 |

Now this seems straight forward, as you progress through the 13-segment displays, byte offset gets incremented by two, and bit offset gets incremented by one. To test the hypothesis, I picked a neighboring segment (j) and tracked the addresses:

| 13-segment display | Address (byte:bit) |

|---|---|

| 1 | 1:5 |

| 2 | 3:6 |

| 3 | 5:7 |

| 4 | 6:0 (!!!) |

| 5 | 8:1 |

| 6 | 10:2 |

| 7 | 12:3 |

| 8 | 14:4 |

As you can see, an interesting thing happened to the segment address on 13-segment display no. 4. Instead of following the pattern, bit address became 0 and byte address got incremented by one, as if it “overflowed”. Afterwards, the already established pattern is continued. This gave me enough information to derive a pattern of how each segment of the 13-segment display changes as you progress through the 13-segment displays:

seg_address calculate_segment(seg_address base_segment, uint8_t offset)

{

const auto new_bit_offset = base_segment.bit + offset;

if (new_bit_offset < 8)

return seg_address{base_segment.byte + (offset * 2), new_bit_offset};

return seg_address{base_segment.byte + (offset * 2 - 1), new_bit_offset - 8};

}

Further testing of this algorithm on other segments within the 13-segment display revealed that this is correct for all 13-segment displays on the LCD. At this point, I knew how to effectively and quite efficiently (memory wise) handle each segment of the display. If you are interested how this looks in practice, you can see the entire map of segment addresses here.

What I did with this thing

Initially I wanted to build a sensory board for my kiddo. If you don’t know what it is - look it up, its actually pretty cool and helps to develop fine motor skills. And as any self-respecting geek, I wanted to make it all cool and interactive (avoiding flashing lights or other sources of over-stimulation, of course!). To build it, I just looked around my junk boxes for buttons, switches and other doodads to put on the board. That’s when I re-discovered this faceplate. It has small-ish buttons, a big rotary encoder and a display, while also being quite sturdy - all things that I need to make an interesting and child-proof toy. To compliment the faceplate, I added a buzzer and made a few simple games that make noises when a button is pressed or a rotary encoder is turned. The entire project can be found here. The most important part is that my kiddo really enjoys the sensory board, so all that effort didn’t go to waste.