Crackme: floppy.img by 2bitsin

So I have this friend Alex. He is one of the best programmers that I know and had the honor to work with. The guy literally lives and breathes bits and bytes. He is also a fan of programming challenges, especially optimization ones. Sometimes he creates his own. One day, he dropped me a file on Discord titled floppy.img and said “solve it”. I put it off for some time due to a busy schedule and that was a grave mistake on my part, because this is the most fun crackme that i’ve solved to date. And You will see why in this post.

Before reading further, if you want to solve it yourself, I’ve asked Alex to put this challenge up on crackmes.one. It is titled “Secret message from a traveller” and you can grab it here. I highly suggest you give it a shot first, it’s really fun.

Analyzing the binary

The file is titled floppy.img and it has the size of 1.44 MiB. One would be wise to assume that this is a raw image dump of a 3½-inch HD floppy diskette. But just to make sure, let’s run file command to see what it finds:

floppy.img: , code offset 0x3b+3, OEM-ID "ERR 401", root entries 224, sectors 2880 (volumes <=32 MB),

sectors/FAT 9, sectors/track 18, serial number 0x117bceb9, label: "INPCWETRUST",

FAT (12 bit), followed by FAT

Interpreting the data, we find that indeed sector and sector/track counts match values one would expect from a 3½ floppy disk. The file command also tels us that it is formatted using FAT12. OEM-ID, serial number and label don’t really matter - read on and you will see why.

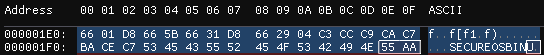

If we were to mount this image, we can see that it contains a single file: secureos.bin. Running file on this file, presents us with a weird output that says:

secureos.bin: OpenPGP Secret Key

This is a bit suspect to me, since opening it in a hex editor didn’t reveal any clues that it has anything to do with OpenPGP. The file did look encrypted though, since the data contained within it didn’t have anything meaningful. To validate that, I decided to run an entropy check using binwalk, which gave me the output:

DECIMAL HEXADECIMAL ENTROPY

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

0 0x0 Rising entropy edge (0.972876)

The file has a pretty high entropy, so this points me to it being encrypted. Ergo, the OpenPGP thing is a red herring - a false detection by libmagic (file). But how can we decrypt it? Let’s dig deeper.

Running the image

As shown in the section above, the image is formatted as FAT (FAT12 to be precise). The FAT file system, besides being a file system as the name implies, has another cool feature - being able to store 448 bytes of bootable code. We can easily check if the image is bootable by opening it in a hex editor and looking at the offset 0x1fe. If it contains the boot signature of 0xaa55, that means the image can be booted. That’s exactly what I did and It confirmed my suspicions - the image does contain bootable code.

So naturally, I tried booting it with qemu for x86 processors:

qemu-system-i386 floppy.img

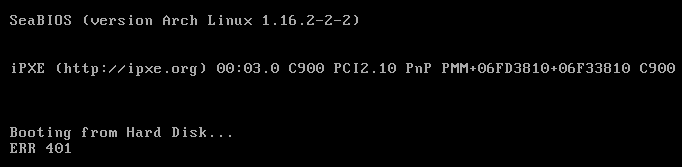

And the result was cryptic and mysterious:

Hitting any key on the keyboard, just prints ERR 401 message again. I tried searching the internet for various combinations of 401 and error, but that led me nowhere, except for the standard HTTP response code of 401 Unauthorized. I confirmed with my friend, that this is indeed the correct reference and knowing the limitations that writing code in a boot sector has (remember, only 448 bytes without loading additional data from the floppy!), I’ll take it (although it still weirds me out seeing it used in this context).

So it’s time to see what exactly the bootable code does and how to bypass the ERR 401 message.

Ghidra time!

My tool of choice for analyzing code is Ghidra and loading bootable images in Ghidra is a little more involved than just opening the .img file. First of all, this is boot code, that means its written for 16 bit Real Mode, because that’s what your x86 CPU only understands as soon as it boots.

Ghidra usually doesn’t detect that it’s 16 bit Real Mode code from the image alone - it has to be selected manually. Luckly, after selecting the type of processor and code that is being used, Ghidra is able to parse and disassemble Real Mode code without any issues.

One interesting thing to note about Real Mode code is that it uses a thing called segmented addressing. It’s a scheme that encodes an address using two registers. The need for it arose, because early x86 processors used a 20 bit address bus, but each register could only store 16 bits, thus not being able to cover the entire addressable memory area. If you are not familiar with segmented addressing, please familiarize yourself with this osdev article. It’s short, to the point and will make understand what’s about to happen next far easier.

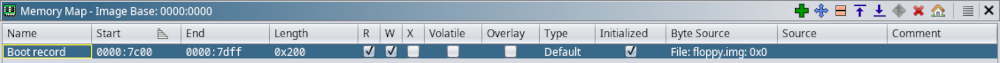

Anyway, back to reversing. After I loaded the image in Ghidra, I wanted to wanted to set up my memory map correctly for convenience and ease of debugging, if I ever need to do that (spoiler alert, I did). By convention, the bootable sector (first 512 bytes of the floppy image) is loaded by the BIOS starting at the memory address 0x0000:0x7c00 (this is how segmented addresses are denoted by the way). I want to reflect that, so I set up my Ghidra’s memory map as such:

Since I only want to analyze the boot sector, I only took the first 512 bytes from the floppy.img file. If I find that the code in the boot sector loads additional data from the floppy, I can always add more to Ghidra’s memory map.

Once that was done, proper analysis can begin. I started the reversing process by locating where the ERR 401 string is located, because that’s the clue that I had. The string is located at address 0x0000:0x7c03, which is actually reserved for the OEM string in the boot record (a structure that defines information about bootable code). I suspect that this was done to save some space. For brevity, I named this location err_string. I also confirmed that there were no other error strings, so this is what I have to work with. Cross-referencing err_string string showed me it’s being used in two locations: 0x0000:0x7d74 and 0x0000:0x7d81, both of which are located inside functions. Let’s take a look at the first one:

0000:7d74 fc CLD

0000:7d75 be 03 7c MOV SI,err_string = "ERR 401"

0000:7d78 e8 06 00 CALL FUN_7d81

0000:7d7b 31 c0 XOR AX,AX

0000:7d7d cd 16 INT 0x16

0000:7d7f cd 19 INT 0x19

We can see here, that the code moves err_string to SI, presumably as an argument, and calls function located at 0x0000:0x7d81, which is the second function where err_string is referenced. Subsequently, it issues two interrupts: INT 0x16 and INT 0x19. To understand what that means, lets take a small detour.

Talking with the BIOS

One of the main goals BIOS is to provide programmers with low-level functionality and abstract as much variation between different hardware as possible. Heck, it’s even in the name Basic Input Output System. To access this functionality, we issue specific software interrupts, which get subsequently picked up by the BIOS and serviced. The software interrupt number that is issued is generally associated with a specific subsystem, such as:

0x10- deals with the video subsystem0x14- serial port access0x16- keyboard access

Some interrupts can be issued as-is. For example, using the instruction INT 0x19 will restart your device. But usually, most interrupts require passing additional information to the BIOS. That is done via registers. AH register usually has special meaning - it is used to denote what functionality is needed from a particular subsystem. Let’s take a look at an example of printing a character at the current cursor (let’s assume that our display mode is currently text):

MOV AH,0x0A # Specify that that we want to print a character on the display at the current cursor position

MOV AL,'H' # Specify which character we want to print. 'H' in this case

XOR BX,BX # No color, default page (don't worry about what that means)

INT 0x10 # Issue the interrupt to the video subsystem

As a result, character H will be printed at the current cursor position.

You can read more about BIOS interrupts and how to use them in this wonderful Wikipedia article. To find out which registers need to be set for specific interrupts, you can use this handy-dandy index from cytime (archived). Also, this website has peak 90’s aesthetics!

Reversing the error message printing functions

Continuing where we left off, now we have enough context to understand what instructions INT 0x16 and INT 0x19 do. Looking at ctyme’s list, we find that:

INT 0x16- whenAHis set to0x00(and it is, becauseAX, which contains registersAHandALis cleared usingXOR AX,AXjust a moment before), read a keypress from the keyboard and store results toAHandAL. If no key is being pressed, code execution is halted until a key is pressedINT 0x19- I already alluded to this in the previous section - it restarts the device

Putting two and two together, it waits for keypress and restarts.

Now, let’s take a look at the function in 0x0000:0x7d81 that gets called:

0000:7d81 50 PUSH AX

0000:7d82 53 PUSH BX

LAB_0000_7d83:

0000:7d83 ac LODSB SI=>err_string # "ERR 401"

0000:7d84 08 c0 OR AL,AL

0000:7d86 74 08 JZ LAB_0000_7d90

0000:7d88 31 db XOR BX,BX

0000:7d8a b4 0e MOV AH,0xe

0000:7d8c cd 10 INT 0x10

0000:7d8e eb f3 JMP LAB_0000_7d83

0000:7d90 5b POP BX

0000:7d91 58 POP AX

0000:7d92 c3 RET

The point of interest is the INT 0x10 instruction with AH being set to 0xe. Referencing ctymes list, we can see that this is also used to print the character located in the AL register, but after the interrupt, the cursor is advanced on the screen. The AL register is set via LODSB SI instruction.

I’d like to take a moment and talk about this instruction, because I think it’s pretty cool. LODSB is a special instruction that is used in string manipulation. It loads data from a DS:source_operand (SI in this case, DS is set to zero, but not shown in this snippet) to AL and it increments or decrements the operand based on the direction flag (DF), upon loading the data. This enables us to iterate over a string.

You can also see that there is a conditional jump at 0x0000:0x7d86 if the loaded character is zero (null terminated) - it’s a terminating condition for the loop. Now we have enough information to figure out what this function does - it actually prints ERR 401 to the screen. Also, this function is only called once in a function we analyzed previously (located at 0x0000:0x7d74) - so I named that function accordingly: error_and_restart.

Debugging the image

Doing a cross-reference of error_and_restart shows that it is being used in three different places. I want to figure out where it fails when ran under Qemu, so I opted to use a debugger. I was advised by the author of this crackme to use the Bochs debugger/emulator if I need to do debugging, because Qemu’s debugging facilities are sub-par for Real Mode code. This is exactly what I did. Setting up Bochs was a bit of a process, especially since I wanted to have a GUI, but eventually I got there. I set a breakpoint at the start of error_and_restart function and let it rip. It tripped and looking at the stacktrace, I found that it got called from 0x0000:0x7d36. The assembly snippet containing relevant instructions is posted below:

0000:7d22 fd STD

0000:7d23 b8 00 f0 MOV AX,0xf000

0000:7d26 8e c0 MOV ES,AX

0000:7d28 31 ff XOR DI,DI

0000:7d2a 8e df MOV DS,DI

0000:7d2c be f2 7d MOV SI,DATA_7df2

0000:7d2f b9 07 00 MOV CX,0x7

LAB_0000_7d32

0000:7d32 ac LODSB SI=>DATA_7df2

0000:7d33 26 00 05 ADD byte ptr ES:[DI],AL

0000:7d36 75 3c JNZ error_and_restart # Gets called for some reason

0000:7d38 47 INC DI

0000:7d39 e2 f7 LOOP LAB_0000_7d32

0000:7d3b fc CLD

To explain what happens here, first of all notice that it is a loop that is implemented using a LOOP instruction. This is a special kind of instruction, that performs a jump if CX register is not equal to zero. After performing a jump, it also decrements the CX register by 1. We can also find that in address 0x0000:0x7d2f, CX is set to 0x7. That means that code between the LOOP instruction and it’s jump label will be executed 7 times.

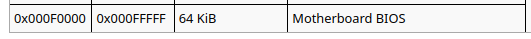

Now, look at the instruction in the loop ADD byte ptr ES:[DI],AL. We are adding a byte located at ES:[DI] to the register AL. Let’s figure out where ES:[DI] points to. DI is initially set to 0x00 via XOR DI,DI, and ES is set to 0xf000 via the AX register. So to answer where ES:[DI] initially points is 0xf000:0x0000. And that tells me absolutely nothing of significance. To make sense of this, I need to figure out what is contained in that address address, since it is not located in this boot sector. We can do that by referencing a memory map of the Real Mode address space, which can be found on osdev. And it just so happens that it’s the beginning of the BIOS rom itself:

Now let’s figure out what data is contained in the AL register. We can find the answer one line above: LODSB SI (see the previous section if you forgot what LODSB does). Following the trail of breadcrumbs, we find that SI is initially set in 0x0000:0x7d2c to be a pointer to some data the boot sector. One thing to note here as well is the STD instruction right at the beginning of this snippet. What this instruction does is it sets the direction flag. Meaning, that when LODSB loads data from DS:SI, it will then decrement SI by one. This means that data to which SI is pointing to will be loaded in a reverse order upon each iteration of the loop.

As a result, we have enough context to figure out what SI should point to - a string of bytes in reverse order. Let’s take a look at the address that is found in DATA_7df2:

0000:7dec cc sdb -52

0000:7ded c9 sdb -55

0000:7dee ca sdb -54

0000:7def c7 sdb -57

0000:7df0 ba sdb -70

0000:7df1 ce sdb -50

0000:7df2 c7 sdb -57

It does confirm the fact that it is 7 bytes, they are all signed negative numbers. Curiously, if you disregard the minus, they seem to fall within the range of printable ASCII. I tried decoding it in reverse order (remember, direction flag is set!) and what I got was this confusing string: 92F6974. It looks meaningless at first, but after searching the internet, I found that is a BIOS product number belonging to an old IBM machine and the code snippet above is a clever way to compare two strings - subtracting each character (stored in BIOS) from it’s compliment (stored in the boot sector). If the result is zero - bytes match. And if at least a single byte doesn’t match, the code jumps to error_and_restart indicating that the machine where the code is running does not have a correct BIOS present.

The answer

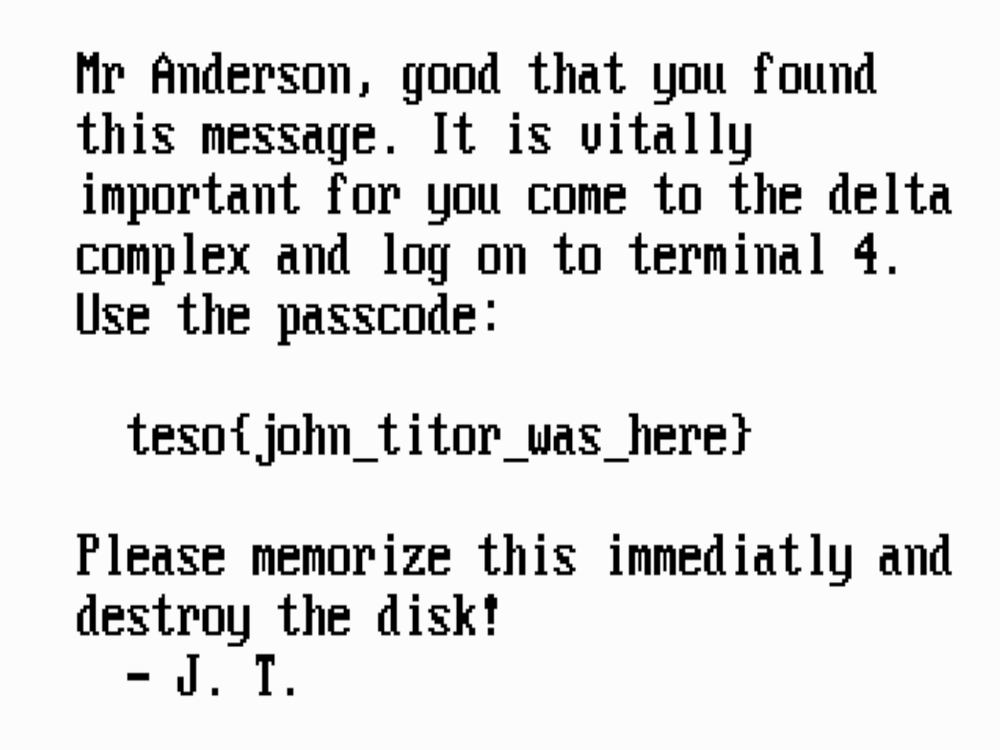

So the answer is pretty simple here, the floppy image needs to be booted from an IBM PS/1 Model 2121 machine, which has a US BIOS with the P/N of 92F9674. Of course I do not have such machine in my possession, so I need to figure out a way to emulate this particular machine. With the help of my friend DuckDuckGo, I stumbled across a project called IBMulator, which can in fact emulate a Model 2121. The necessary BIOS image and other goodies was found in the ps1stuff.wordpress.com blog. After setting everything up, tweaking the boot settings with CUSTOMIZ.EXE, “inserting” the floppy (well actually, loading floppy.img in the emulator) and waiting a bit, I was presented with some static noise which eventually turned into text containing a flag.

The challenge was solved.

What about secureos.bin

Remember at the start of this post, I mentioned that there is a file in the floppy image titled secureos.bin? How does it relate to this challenge? I snooped around the code and found that before doing this BIOS check, it actually loads this file into memory. It then decrypts it using contents of the BIOS as a symetric key and stores the decrypted file at 0x8000:0x0000. If the BIOS check that we reversed succeeds, It then jumps to 0x8000:0x0000, thus executing the code that was in the encrypted file. So this BIOS check is a nice way to inform that the file was decrypted correctly.

Conclusions … for now

This was an amazing crackme, I had a blast solving it. At the start, I basically knew nothing about boot sector code and barely had a grasp of segmented memory addressing. After solving this, I feel much more competent in my ability to read and understand Real Mode code. But I am not done with this challenge. My friend mentioned that there is still some fun to be had with the cryptography algorithm that is used to decrypt secureos.bin, so I set myself a challenge - write a script that decrypts the binary and packages it into another floppy image which can boot on any machine (or emulator). Stay tuned for part 2.

And of course massive thanks to my friend Alex for not only making this challenge, but also providing me hints how to solve it and even for helping me write this article.